By: Ceilidh Kern, Columbia Missourian

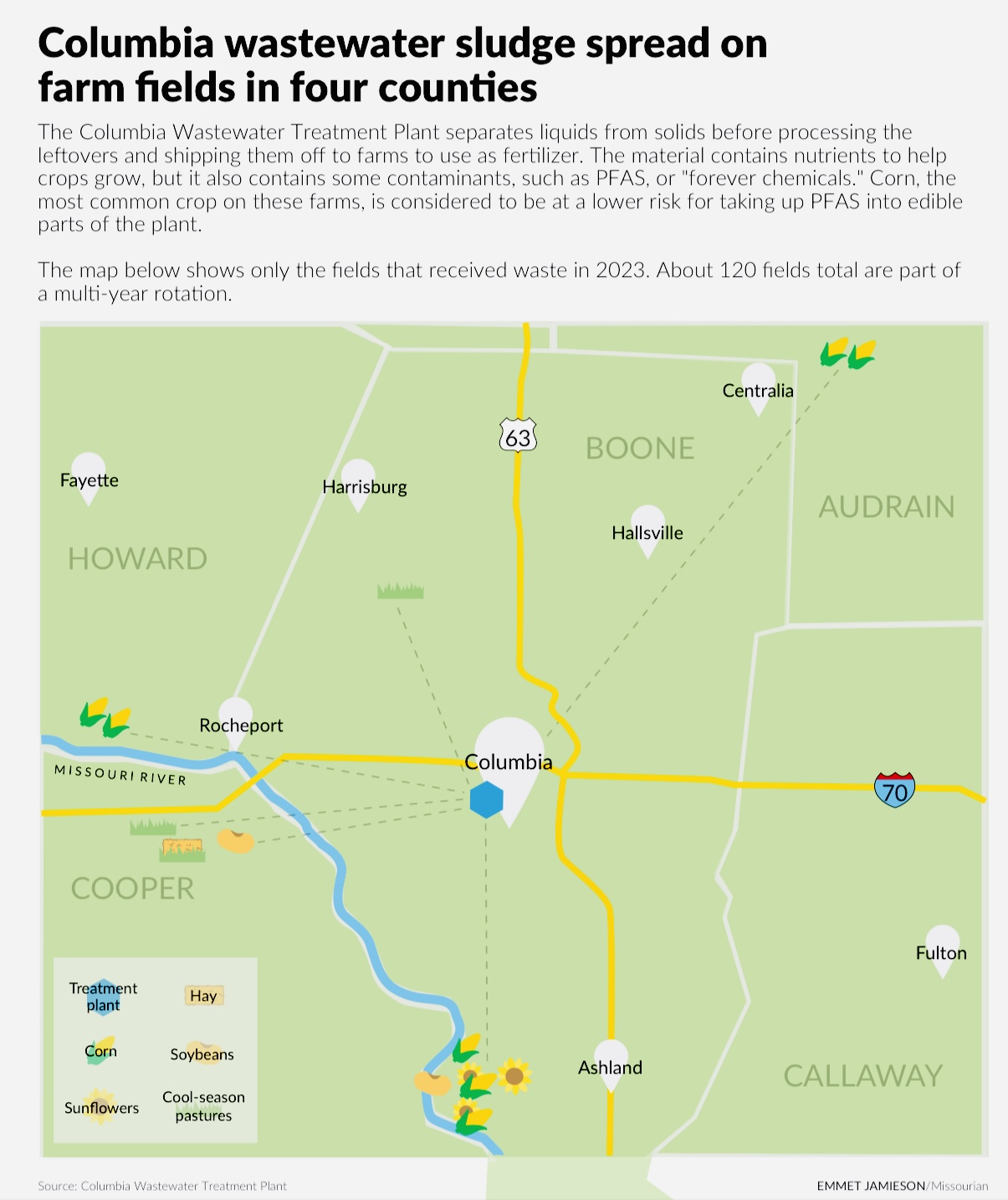

For more than 40 years, the city of Columbia has applied tens of thousands of tons of wastewater sludge as fertilizer on farms across mid-Missouri. In January, the City of Ashland discussed adopting the practice as an incentive to its recent dump trailer purchase, stating that the new trailer would enable the Ashland Public Works Department to transport wastewater biosolid sludge to nearby farms to be used as fertilizer.

Now, it turns out its sludge contains “forever chemicals” known to cause cancer and other health problems. The city has known this for almost a year but has yet to share the news with the 30 farmers who apply the sludge to 120 fields.

Columbia is one of hundreds of cities across the United States grappling with the issue of emerging contaminants in fertilizer made from sewage. Federal regulations are still potentially years away, leaving states and cities in limbo.

In states like Maine and Michigan, the government shut down farms after the land was found to have high levels of forever-chemical contamination following years of wastewater-sludge application.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency promotes the use of sludge, also called biosolids, as fertilizer because it contains organic matter and nutrients, but an agency assessment found that sludge also contains forever chemicals, pharmaceuticals, microplastics and other contaminants.

Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, an environmental advocacy group, announced its intent to sue the agency over forever chemicals in sludge earlier this year. The Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association will join the suit.

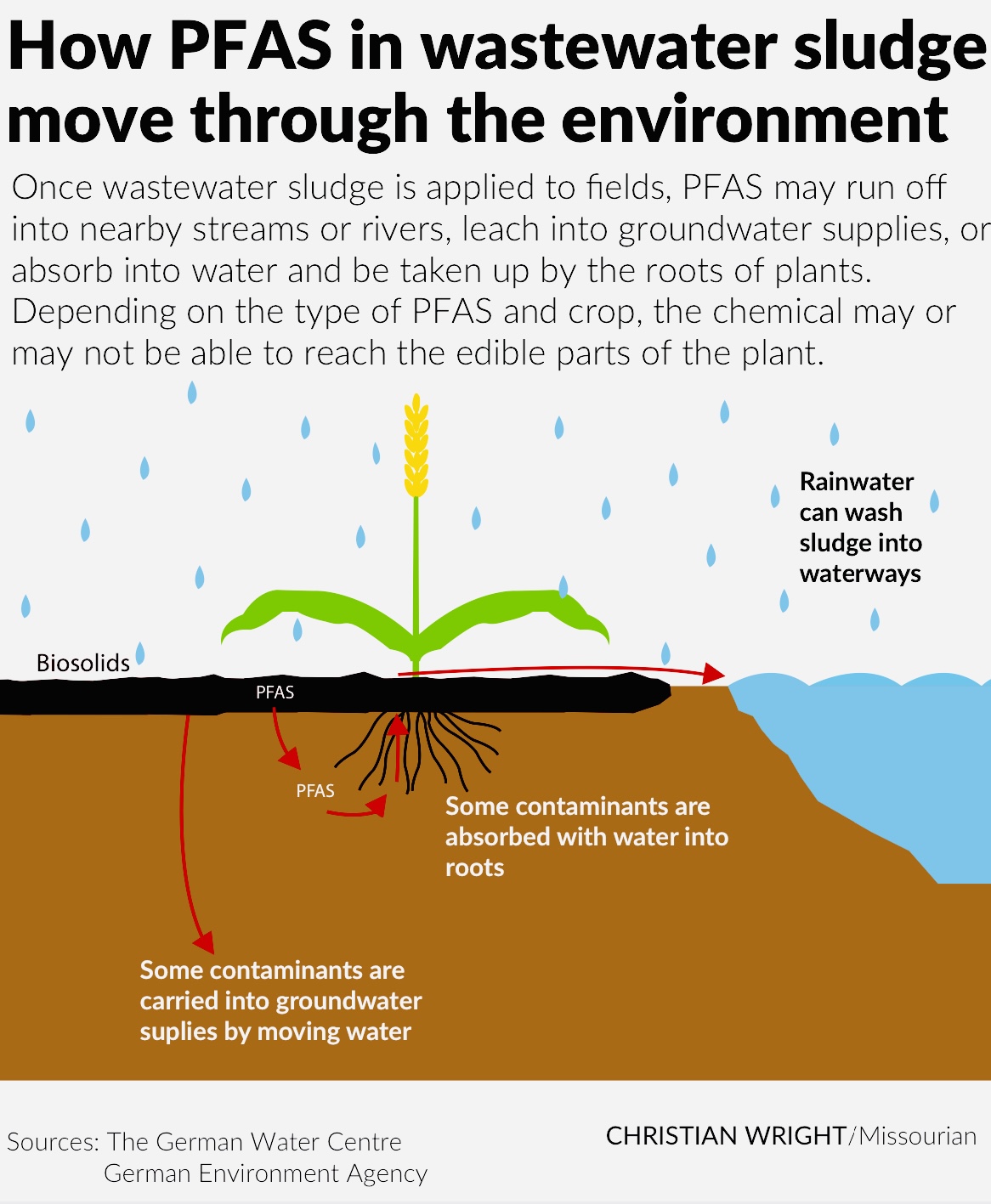

Forever chemicals, also known as PFAS — short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — are often used in consumer products for their indestructibility and ability to resist heat, water and oil. Once in the body, they’ve been linked with greater risk of certain cancers, reduced vaccine efficacy and decreased fertility, among other issues.

While Columbia’s test results show relatively low amounts of PFAS in sludge compared to places like Michigan or Maine, some experts say there is no safe level and sludge use should be banned.

“They should not be land-applied, full stop,” said Kyla Bennett, director of PEER. “The short-term solution is to just say no, don’t spread this stuff on land, particularly on farms.”

“Every single state where these biosolids are spread is going to end up contaminating the land,” Bennett added. “Everywhere this is spread, we’re going to have a PFAS problem.”

From sewer to field

Wastewater sludge coats blades on a tractor April 25 at a farm in Columbia. Workers applied the material at a controlled rate.

Tucked away in the southwestern corner of Columbia, the city’s wastewater treatment plant is marked by a gas flare in front of the facility, burning off excess methane released during treatment. Walking among the treatment tanks, a distinctly bitter smell hits the back of the nose, a scent that settles over neighborhoods around the plant from time to time.

The smell is understandable, given the plant’s task of treating sewage, a process that begins when wastewater arrives at the plant and liquids are separated from solids. The former is treated and released into the nearby wetland, while the latter is processed and turned into sludge, a substance that looks like black potting soil, but stickier. The sludge is then carried by truck to farms, where it is dumped and tilled into the ground.

Nationwide, incineration and landfilling are popular approaches to handling the leftovers from wastewater treatment, but 40% of the country’s residual waste is applied to fields, with another 11% undergoing additional treatment so it can be sold as fertilizer, according to 2018 data from the National Biosolids Data Project.

In 2018, nearly 30% of Missouri wastewater treatment plants‘ residual waste went toward agricultural sludge. While St. Louis and Kansas City both incinerate their waste, many Missouri cities and towns, such as Springfield and Columbia, choose to apply it to land, and some, including Sedalia and Cape Girardeau, have upgraded their processing enough to sell their waste.

The farmer perspective

Columbia’s program began more than four decades ago as a way to make use of the city’s waste and offer free fertilizer to local farmers.

Steve Diederich and his brothers, who live outside of Hartsburg, had wanted to participate in Columbia’s sludge program since the Great Flood of 1993, when rising waters from the nearby Missouri River coated their fields with sand that couldn’t hold water long enough to grow crops.

They were finally able to join the program around 1998. As they incorporated more sludge over time, they saw an improvement in the soil’s nutrient makeup and its ability to hold water.

“We took ground that even under irrigation would raise nothing and, by applying sludge to it, it’ll all raise something now,” Diederich said, adding, “I’m a big fan of sludge.”

Between the nutrients already in the soil and those added by the sludge, Diederich said he only has to add some nitrogen and potash — a mineral containing potassium, a basic ingredient in fertilizer — to his fields. Overall, he estimated the program saves him $20,000 a year in commercial fertilizer and application costs.

Diederich is one of 30 landowners participating in Columbia’s program, which land-applies sludge to 120 fields over the course of several-year cycles, said Greg Mabrey, a sewer utility supervisor at the wastewater treatment plant.

People at the plant told him they had detected some at very low levels, “but there’s no regulations that tell them what that means, so they don’t know what to do.”

Diederich said he’s not particularly worried about contamination from forever chemicals. He said he suspects periodic flooding of the Missouri River introduces more PFAS to his fields than sludge, and he trusts the plant’s testing program and its assessment of the risk.

“I’m not too concerned about the forever chemicals. If they’re that inert, I don’t really think they’re going to hurt people,” he said. “There are probably some bad ones out there that may affect you health wise, but it’s all too new, and nobody knows.”

Erin Keys, assistant director of sewer and storm water utilities for the city’s Utilities Department, said the city hasn’t shared its test results with farmers because it is waiting on additional information about the impacts and risks, as well as federal regulations.

However, she said that since regulations are still several years away, once there is more information available about risks — an EPA risk assessment report is expected by the end of this year — staff will create informational materials to distribute to farmers working with the program so they understand the potential threat.

A lack of federal guidance

What counts as “high” levels of PFAS is still up for debate. For drinking water, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a new regulation in April requiring utilities to treat their water if certain kinds of PFAS, including PFOS and PFOA, are detected at four parts per trillion, or about four drops of water in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

Meanwhile, the agency’s health advisory, a non-enforceable recommendation, says lifetime exposure to as little as 0.004 ppt of PFOS — a thousandth of the new regulatory limit — in drinking water could cause negative health effects.

There are currently no proposed federal regulations on PFAS in sludge, though some states, like Michigan and Maine, have released their own rules.

In Michigan, sludge with PFOA or PFOS below 20 parts per billion (20,000 ppt) is considered safe enough to land-apply, while in Maine, the land-application of sludge was completely banned in 2022 due to concerns about PFAS contamination that shut down dairy farms in the state.

Columbia’s sludge falls shy of Michigan’s standards, as test results from March 2023 measured PFOS at 7.83 ppt and could not detect PFOA, though both were found in the wetlands where the wastewater plant releases its treated water, measuring 4.67 and 3.87 ppt, respectively.

Although federal regulations set limits for heavy metals, pathogens and excessive nutrients in sludge, they say nothing about emerging contaminants like PFAS, which Columbia detected in its drinking water wells in December.

While federal policymakers work toward regulating PFAS in sludge, state and local governments are on their own to require testing or set limits.

In the meantime, “the EPA recommends that states monitor sewage sludge for PFAS contamination, identify likely industrial discharges of PFAS chemicals, and implement industrial pretreatment requirements where appropriate,” said Cathy Milbourn, an EPA press officer, in an emailed statement.

Columbia has only a handful of such facilities. Keys said the city regularly works with local manufacturers to monitor what kinds of substances they’re releasing with their wastewater and require pretreatment — paid for by the facilities, not the city — when necessary.

The city is not currently requiring testing or pretreatment for PFAS, but Keys said one facility, which she would not name, has been voluntarily testing for them. She would not confirm whether the company shared its results with the city.

As Columbia waits for federal guidance on how to regulate forever chemicals and other emerging contaminants in wastewater and sludge, Keys said she wants regulators to focus on the companies producing PFAS instead of the facilities that treat their polluted water.

The cost of hauling the waste to the city’s landfill, the city’s only alternative, would equal “in the hundreds of thousands (of dollars), probably close to a million,” she said.

“The levels that we’re seeing, which are extremely minor, I don’t know, it seems like it will be very expensive for a community like Columbia to treat that,” Keys said. “We wouldn’t even be able to treat it. We would just be transferring the problem to the landfill.”

This article was originally published by the Columbia Missourian and has been reprinted with permission. View entire series here.

Facebook Comments